Tumors are made up of millions of cells, and removing all of these cells surgically or eliminating them with medication becomes much more difficult after the cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

Now, in a study published this month in iScience, an interdisciplinary team comprising researchers from the Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo, Kanazawa University, Institute of Science Tokyo, and Kyorin University School of Medicine has determined exactly how these tumor cells are able to accomplish intrabody travel to form tumors elsewhere.

Small clusters of circulating tumor cells, which are cells that detach from tumors and circulate around the bloodstream, have been detected in the blood of patients with advanced cancer. These circulating tumor cells are much more likely to cause metastases than individual cells.

"Clinical observations demonstrate that metastases are induced by circulating tumor cell clusters, but it has remained unclear how these clusters cross the robust endothelial barrier of the blood vessel to enter our body's circulation," explains senior author Yukiko Matsunaga, Ph.D., a professor at The University of Tokyo.

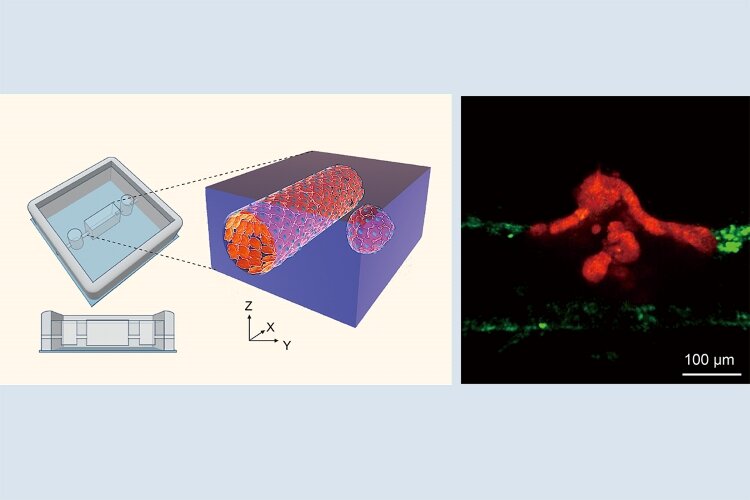

To address this, the researchers developed a three-dimensional, in vitro culture system containing an artificial blood vessel and intestinal tumor organoids, small pieces of tumor-like tissue. The researchers carefully positioned the organoids either right next to the blood vessel or slightly away from it. They then used live-imaging techniques to observe interactions between the tumor cells and the blood vessel to determine how tumor cell clusters infiltrate blood vessels.

"The results were striking", agree Yukinori Ikeda, Ph.D. and Makoto Kondo, Ph.D., co-lead authors of the study. "We observed clusters of tumor cells migrating toward the vessel, disrupting the vessel cell wall to facilitate entry, and then being dispersed once inside the blood vessel."

The researchers found that cells in the blood-vessel wall expressed high levels of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and activin in the presence of a migrating tumor cell cluster. This was associated with endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, i.e., the vessel wall losing its endothelial characteristics, in disrupted areas of the vessel wall. This suggests that the clusters induced partial dismantling of the blood-vessel wall.

"Our findings suggest that these tumor cell clusters, after detaching from primary tumors, move toward blood vessels, take over a part of the blood-vessel wall, and disperse via the bloodstream to facilitate distal metastasis," explains Matsunaga.

Given that metastasis is associated with a worse prognosis, preventing clusters of circulating tumor cells from entering the bloodstream could improve outcomes in patients with advanced cancer. The 3D in vitro system developed in this study will be valuable for developing treatment strategies that specifically target the blood-vessel infiltration mechanism of these clusters.

The article, "A tumor-microvessel on-a-chip reveals a mechanism for cancer cell cluster intravasation," was published in iScience at DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.112517.

Research Contact

Yukiko Matsunaga, Professor

Institute of Industrial Science, the University of Tokyo

Tel:+81-3-5452-6382

E-mail:mat-info (Please add "@iis.u-tokyo.ac.jp" to the end)